Hon. T. T. Bouldin, a slave-holder, and member of Congress from Virginia, in a speech in Congress, Feb. 16, 1835. Mr. Bouldin said "he knew that many negroes had died from exposure to weather,'' and added, "they are clad in a flimsy fabric, that will turn neither wind nor water.''

George Buchanan, M. D., of Baltimore, member of the American Philosophical Society, in an oration at Baltimore, July 4, 1791. "The slaves, naked and starved, often fall victims to the inclemencies of the weather.''

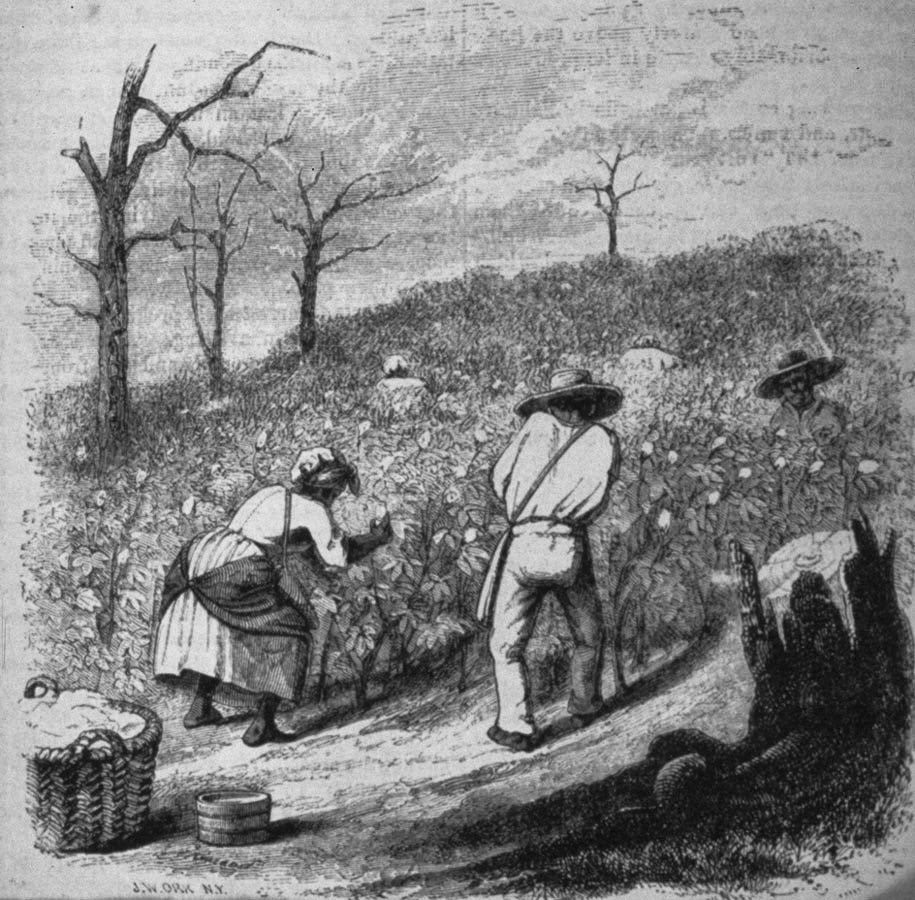

Wm. Savery of Philadelphia an eminent Minister of the Society of Friends, who went through the Southern states in 1791, on a religious visit: after leaving Savannah, Ga., we find the following entry in his journal, 6th, month, 28, 1791. "We rode through many rice swamps, where the blacks were very numerous, great droves of these poor slaves, working up to the middle in water, men and women nearly naked.''

Rev. John Rankin, of Ripley, Ohio, a native of Tennessee. "In every slave-holding state, many slaves suffer extremely, both while they labor and while they sleep, for want of clothing to keep them warm.''

John Parrish, late of Philadelphia, a highly esteemed minister in the Society of Friends, who travelled through the South in 1804. "It is shocking to the feelings of humanity, in travelling through some of those states, to see those poor objects, [slaves,] especially in the inclement season, in rags, and trembling with the cold...They suffer them, both male and female, to go without clothing at the age of ten and twelve years.''

Rev. Phineas Smith, Centreville, Allegany, Co., N. Y. Mr. S. has just returned from a residence of several years at the south, chiefly in Virginia, Louisiana, and among the American settlers in Texas. "The apparel of the slaves, is of the coarsest sort and exceedingly deficient in quantity. I have been on many plantations, where children of eight and ten years old, were in a state of perfect nudity. Slaves are in general wretchedly clad .''

Wm. Ladd, Esq., of Minot, Maine, recently a slaveholder in Florida. "They were allowed two suits of clothes a year, viz. one pair of trowsers with a shirt or frock of osnaburgh for summer; and for winter, one pair of trowsers, and a jacket of negro cloth, with a baize shirt and a pair of shoes. Some allowed hats, and some did not; and they were generally, I believe, allowed one blanket in two years. Garments of similar materials were allowed the women.''

Mr. Stephen E. Malthy, Inspector of provisions, Skeneateles, N. Y., who resided sometime in Alabama. "I was at Huntsville, Alabama, in 1818-19, I frequently saw slaves on and around the public square, with hardly a rag of clothing on them, and in a great many instances with but a single garment both in summer and in winter; generally the only bedding of the slaves was a blanket.''

Reuben G. Macy, Hudson, N. Y. member of the Society of Friends, who resided in South Carolina, in 1818 and 19. "Their clothing consisted of a pair of trowsers and jacket, made of 'negro cloth.' The women a petticoat, a very short 'short-gown,' and nothing else, the same kind of cloth; some of the women had an old pair of shoes, but they generally went barefoot.''

Mr. Lemuel Sapington, of Lancaster, Pa., a native of Maryland, and formerly a slaveholder "Their clothing is often made by themselves after night, though sometimes assisted by the old women, who are no longer able to do out-door work; consequently it is harsh and uncomfortable. And I have very frequently seen those who had not attained the age of twelve years go naked.''

Philemon Bliss, Esq., a lawyer in Elyria, Ohio, who lived in Florida in 1834 and 35. "It is very common to see the younger class of slaves up to eight or ten without any clothing, and most generally the laboring men wear no shirts in the warm season. The perfect nudity of the younger slaves is so familiar to the whites of both sexes, that they seem to witness it with perfect indifference. I may add that the aged and feeble often suffer from cold.''

Richard Macy, a member of the Society of Friends, Hudson, N. Y., who has lived in Georgia. "For bedding each slave was allowed one blanket, in which they rolled themselves up. I examined their houses, but could not find any thing like a bed.''

W. C. Gildersleeve, Esq., Wilkesbarre, Pa., a native of Georgia. "It is an every day sight to see women as well as men, with no other covering than a few filthy rags fastened above the hips, reaching midway to the ankles. I never knew any kind of covering for the head given. Children of both sexes, from infancy to ten years are seen in companies on the plantations, in a state of perfect nudity. This was so common that the most refined and delicate beheld them unmoved.''

Mr. William Leftwich, a native of Virginia, now a member of the Presbyterian Church, in Delhi, Ohio. "The only bedding of the slaves generally consists of two old blankets.''

From American Slavery As It Is

Theodore Weld

New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1839

,+vol.+19,+p.+726;+wiyh+article+by+T.+Addison+Richards,+The+Rice+Lands+of+the+South+(pp.+721-38)..jpg)

,+vol.+19,+p.+729;+with+article+by+T.+Addison+Richards,+The+Rice+Lands+of+the+South+(pp.+721-38)..jpg)

,+vol.+14,+p.+49..jpg)

,+vol.+3,+p.+307.jpg)

,+vol_+14,+p_+438_.jpg)

,+p.232.+(Copy+in+Special+Collections+Department,+University+of+Virginia+Library).jpg)

,+p_68_.jpg)

,+p.+177..jpg)

,+vol.+9,+p.+760.+(Copy+in+Special+Collections+Department,+University+of+Virginia+Library).jpg)

,+p_+8_+2.jpg)

,+vol_+19,+p_+726;.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

+1848-1912+Georgia.jpg)

,+p.+620..jpg)

,+p.+621.jpg)

,+p.621;.jpg)

,.jpg)

+Stacking+Wheat+in+Culpepper,+Virginia+1863.jpg)

,.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)