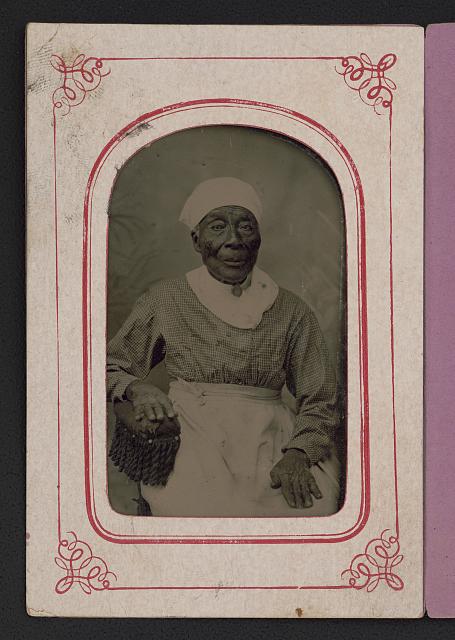

Paulina W Davis

This leaves me at liberty to occupy your attention for a few moments with some general reflections upon the attitude and relations of our movement to our times and circumstances, and upon the proper spirit and method of promoting it. I do not even intend to treat these topics formally, and I do not hope to do it successfully; for nothing less than a complete philosophy of reform could answer such inquiries, and that philosophy, it is very certain, the world has not yet discovered.

Human rights, and the reasons on which they rest, are not difficult of comprehension. The world has never been ignorant of them, nor insensible to them; and human wrongs and their evils are just as familiar to experience and as well understood; but all this is not enough to secure to mankind the possession of the one, or to relieve them from the felt burden and suffering of the other. A creed of abstract truths, or a catechism of general principles, and a completely digested list of grievances, combined, are not enough to adjust a practical reform to its proper work, else Prophets and Apostles and earnest world-menders in general would have been more successful, and left us less to wish and to do.

It is one thing to issue a declaration of rights[2]or a declaration of wrong to the world, but quite another thing wisely and happily to commend the subject to the world's acceptance, and so to secure the desired reformation. Every element of success is, in its own place and degree, equally important; but the very starting point is the adjustment of the reformer to his work, and next after that is the adjustment of his work to those conditions of the times which he seeks to influence.

Those who prefer the end in view to all other things, are not contented with their own zeal and the discharge of their duty to their conscience. They desire the highest good for their follow-beings, and are not satisfied with merely clearing their own skirts; and they esteem martyrdom a failure at least, if not a fault, in the method of their action. It is not the salvation of their own souls they are thinking of, but the salvation of the world; and they will not willingly accept a discharge or a rejection in its stead. It is their business to preach righteousness and rebuke sin, but they have no quarrel with "the world that lieth in wickedness," and their mission is not merely to judge and condemn, but to save alike the oppressor and the oppressed. Right principles and conformable means are the first necessities of a great enterprise, but without right apprehensions and tempers and expedient methods, the most beneficent purposes must utterly fail. Who is sufficient for these things?

Divine Providence has been baffled through all the ages of disorder suffering for want of fitting agents and adapted means. Reformations of religion have proved but little better than the substitution of a new error for an old one, and civil revolutions have resolved themselves into mere civil insurrections, until history has become but a monument of buried hopes.

The European movement of 1848[3] was wanting neither in theory nor example for its safe direction, but it has nevertheless almost fallen into contempt.

We may not, therefore, rely upon a good cause and good intentions alone, without danger of deplorable disappointment.

The reformation which we purpose, in its utmost scope, is radical and universal. It is not the mere perfecting of a progress already in motion, a detail of some established plan, but it is an epochal movement-the emancipation of a class, the redemption of half the world, and a conforming re-organization of all social, political, and industrial interests and institutions. Moreover, it is a movement without example among the enterprises of associated reformations, for it has no purpose of arming the oppressed against the oppressor, or of separating the parties, or of setting up independence, or of severing the relations of either.

Its intended changes are to be wrought in the intimate texture of all societary organizations, without violence, or any form of antagonism. It seeks to replace the worn out with the living and the beautiful, so as to reconstruct without overturning, and to regenerate without destroying; and nothing of the spirit, tone, temper, or method of insurrection is proper or allowable to us and our work.

Human societies have been long working and fighting their way up from what we scornfully call barbarism, into what we boastfully call modern civilization; but, as yet, the advancement has been chiefly in ordering and methodizing the lower instincts of our nature, and organizing society under their impulses. The intellect of the masses has received development, and the gentler affections have been somewhat relieved from the dominion of force; but the institutions among men are not yet modelled after the highest laws of our nature. The masterdom of the strong hand and bold spirit is not yet over, for men have not yet established all those natural claims against each other, which seem to demand physical force and physical courage for their vindication. But the age of war is drawing towards a close, and that of peace (whose methods and end alike are harmony) is dawning, and the uprising of womanhood is its prophecy and foreshadow.

The first principles of human rights have now for a long time been abstractly held and believed, and both in Europe and America whole communities have put them into practical operation in some of their bearings. Equality before the law, and the right of the governed to choose their governors, are established maxims of reformed political science; but in the countries most advanced,[4] these doctrines and their actual benefits are as yet enjoyed exclusively by the sex that in the battle-field and the public forum has wrenched them from the old time tyrannies. They are yet denied to Woman, because she has not yet so asserted or won them for herself; for political justice pivots itself upon the barbarous principle that "Who would be free, themselves must strike the blow." Its furthest progress toward magnanimity is to give arms to helplessness. It has not yet learned to give justice . For this rule of barbarism there is this much justification, that although every human being is naturally entitled to every right of the race, the enjoyment and administration of all rights require such culture and conditions in their subject as usually lead him to claim and struggle for them; and the contented slave is left in slavery, and the ignorant man in darkness, on the inference that he cannot use what he does not desire. This is indeed true of the animal instincts, but it is false of the nobler soul; and men must learn that the higher faculties must be first awakened, and then gratified, before they have done their duty to their race. The ministry of angels to dependent humanity is the method of Divine Providence, and among men the law of heaven is, that the "elder shall serve the younger." But let us not complain that the hardier sex overvalue the force which heretofore has figured most in the world's affairs. "They know not what they do"[5] is the apology that crucified womanhood must concede in justice and pity to the wrong doers. In the order of things, the material world was to be first subdued. For this coarse conflict, the larger bones and stronger sinews of manhood are especially adapted, and it is a law of muscles and of all matter that might shall overcome right. This is the law of the vegetable world, and it is the law of the animal world, as well as the law of the animal instincts and of the physical organization of men; but it is not the law of spirit and affection. They are of such a nature as to charge themselves with the atonement for all evils, and to burden themselves with all the sufferings which they would remove.

This wisdom is pure, and peaceable, and gentle, and full of mercy and of good fruits.

Besides the feebler frame, which under the dynasty of muscles is degraded, there remains, even after justice has got the upper hand of force in the world's judgments, a mysterious and undefined difference of sex that seriously embarrasses the question of equality; or, if that is granted, in terms of equal fitness for avocations and positions which heretofore have been the monopoly of men. Old ideas and habits of mind survive the facts which produced them, as the shadows of night stretch far into the morning, sheltered in nooks and valleys from the rising light; and it is the work of a whole creation-day to separate the light from the darkness.

The rule of difference between the sexes must be founded on the traits which each estimates most highly in the other; and it is not at all wonderful that some of woman's artificial incapacities and slaveries may seem to be necessary to some of her excellencies; just as the chivalry that makes man a butcher of his kind still glares like a glory in the eyes of admiring womanhood, and all the more because it seems so much above and unlike her own powers and achievements. Nature does not teach that men and women are unequal, but only that they are unlike; an unlikeness so naturally related and dependent that their respective differences by their balance establish, instead of destroying, their equality.

Men are not in fact, and to all intents, equal among themselves, but their theoretical equality for all the purposes of justice is more easily seen and allowed than what we are here to claim for women. Higher views, nicer distinctions, and a deeper philosophy are required to see and feel the truths of woman's rights; and besides, the maxims upon which men distribute justice to each other have been battle-cries for ages, while the doctrine of woman's true relations in life is a new science, the revelation of an advanced age, - perhaps, indeed, the very last grand movement of humanity towards its highest destiny, - too new to be yet fully understood, too grand to grow out of the broad and coarse generalities which the infancy and barbarism of society could comprehend.

The rule of force and fraud must be well nigh overturned, and learning and religion and the fine arts must have cultivated mankind into a state of wisdom and justice tempered by the most beneficent affections, before woman can be fully installed in her highest offices. We must be gentle with the ignorance and patient under the injustice which old evils induce. Long suffering is a quality of the highest wisdom, and charity beareth all things for it hopeth all things. It will be seen that I am assuming the point that the redemption of the inferior, if it comes at all, must come from the superior. The elevation of a favored caste can have no other providential purpose than that, when it is elevated near enough to goodness and truth, it shall draw up its dependents with it.

But, however this may be in the affairs of men as they are involved with each other, it is clearly so in the matter of woman's elevation. The tyrant sex, if such we choose to term it, holds such natural and necessary relations to the victims of injustice, that neither rebellion nor revolution, neither defiance nor resistance, nor any mode of assault or defence incident to party antagonism, is either possible, expedient, or proper. Our claim must rest on its justice, and conquer by its power of truth. We take the ground, that whatever has been achieved for the race belongs to it, and must not be usurped by any class or caste. The rights and liberties of one human being cannot be made the property of another, though they were redeemed for him or her by the life of that other; for rights cannot be forfeited by way of salvage, and they are in their nature unpurchasable and inalienable.

We claim for woman a full and generous investiture of all the blessings which the other sex has solely or by her aid achieved for itself. We appeal from men's injustice and selfishness to their principles and affections.

For some centuries now, the best of them have been asserting, with their lives, the liberties and rights of the race; and it is not for the few endowed with the highest intellect, the largest frame, or even the soundest morals, that the claim has been maintained, but broadly and bravely and nobly it has been held that wherever a faculty is given, its highest activities are chartered by the Creator, and that all objects alike - whether they minister to the necessities of our animal life or to the superior powers of the human soul and so are more imperatively needed, because nobler than the bread that perishes in the use - are, of common right, equally open to ALL; and that all artificial restraints, for whatever reason imposed, are alike culpable for their presumption, their folly, and their cruelty.

It is pitiable ignorance and arrogance for either man or woman now to prescribe and limit the sphere of woman. It remains for the greatest women whom appropriate culture, and happiest influences shall yet develop, to declare and to prove what are woman's capacities and relations in the world.

I will not accept the concession of any equality which means identity or resemblance of faculty and function. I do not base her claims upon any such parallelism of constitution or attainment. I ask only freedom for the natural unfolding of her powers, the conditions most favorable for her possibilities of growth, and the full play of all those incentives which have made man her master, and then, with all her natural impulses and the whole heaven of hope to invite, I ask that she shall fill the place that she can attain to, without settling any unmeaning questions of sex and sphere, which people gossip about for want of principles of truth, or the faculty to reason upon them.

But it is not with the topics of our reform and the discussion of these that I am now concerned. It is of its position in the world's opinion, and the causes of this, that I am thinking; and I seek to derive hints and suggestions as to the method and manner of successful advocacy, from the inquiry. Especially am I solicitous that the good cause may suffer no detriment from the theoretical principles its friends may assume, or the spirit with which they shall maintain them. It is fair to presume that such causes as have obscured these questions in the general judgment of the governing sex, must also more or less darken the counsels of those most anxious for truth and right. If our demand were simply for chartered rights, civil and political, such as get acknowledgment in paper constitutions, there would be no ground of doubt. We could plead our common humanity, and claim an equal justice. We might say that the natural right of self-government is so clearly due to every human being alike, that it needs no argument to prove it; and if some or a majority of women would not exercise this right, this is no ground for taking it from those who would. And the right to the control and enjoyment of her own property and partnership in all that she helps her husband to earn and save, needs only to be stated to command instant assent. Her appropriate avocations might not be so easily settled that a programme could be completed on theoretical principles merely; but we need discuss no such difficulties while we ask only for liberty of choice, and opportunities of adaptation; and the question of her education is solved by the simple principle, that whatever she can receive is her absolute due.

Yet all these points being so easily disposed of, so far as they are mere matters of controversy, the advocates of the right need none the less the wisest and kindest consideration for all the resistance we must encounter, and the most forbearing patience under the injustice and insolence to which we must expose ourselves. And we can help ourselves to much of the prudence and some of the knowledge we shall need, by treating the prejudices of the public as considerately as if they were principles, and the customs of society as if they once had some temporary necessity, and so meet them with the greater force for the claim to respect which we concede to them. For a prejudice is just like any other error of judgment, and a custom has sometimes had some fitness to things more or less necessary, and is not an utter absurdity, even though the reason on which it was based is lost or removed. Who shall say that there is nothing serious, or respectable, or just, in the repugnance with which our propositions are received? The politician who knows his own corruption may be excused for an earnest wish to save his wife and daughter from the taint, and he must be excused, too, for not knowing that the corruption would be cured by the saving virtue which he dreads to expose to risk.

There may be real though very foolish tenderness in the motive which refuses to open to woman the trades and professions that she could cultivate and practice with equal profit and credit to herself. The chivalry that worships womanhood is not mean, though it at the same time enslaves the objects of its overfond care.

And it is even possible that men may deprive women of their property and liberties, personal and political, with the kindly purpose of accommodating their supposed incapacities for the offices and duties of human life. Harsh judgments and harsh words will neither weaken the opposition, nor strengthen our hands. Our address is to the highest sentiment of the times; and the tone and spirit due to it and becoming in ourselves, are courtesy and respectfulness. Strength and truth of complaint, and eloquence of denunciation, are easy of attainment; but the wisdom of affirmative principles and positive science, and the adjustment of reformatory measures to the exigencies of the times and circumstances, are so much the more useful as they are difficult of attainment. A profound expediency, as true to principle as it is careful of success, is, above all things, rare and necessary. We have to claim liberty without its usually associated independence. We must insist on separate property where the interests are identical, and a division of profits where the very being of the partners is blended. We must demand provisions for differences of policy, where there should be no shadow of controversy; and the free choice of industrial avocations and general education, without respect to the distinctions of sex and natural differences of faculty.

In principle these truths are not doubtful, and it is therefore not impossible to put them in practice, but they need great clearness in system and steadiness of direction to get them allowance and adoption in the actual life of the world. The opposition should be consulted where it can be done without injurious consequences. Truth must not be suppressed, nor principles crippled, yet strong meat should not be given to babes. Nor should the strong use their liberties so as to become a stumbling block to the weak. Above all things, we owe it to the earnest expectation of the age, that stands trembling in mingled hope and fear of the great experiment, to lay its foundations broadly and securely in philosophic truth, and to form and fashion it in practical righteousness. To accomplish this, we cannot be too careful or too brave, too gentle or too firm; and yet with right dispositions and honest efforts, we cannot fail of doing our share of the great work, and thereby advancing the highest interests of humanity.

This leaves me at liberty to occupy your attention for a few moments with some general reflections upon the attitude and relations of our movement to our times and circumstances, and upon the proper spirit and method of promoting it. I do not even intend to treat these topics formally, and I do not hope to do it successfully; for nothing less than a complete philosophy of reform could answer such inquiries, and that philosophy, it is very certain, the world has not yet discovered.

Human rights, and the reasons on which they rest, are not difficult of comprehension. The world has never been ignorant of them, nor insensible to them; and human wrongs and their evils are just as familiar to experience and as well understood; but all this is not enough to secure to mankind the possession of the one, or to relieve them from the felt burden and suffering of the other. A creed of abstract truths, or a catechism of general principles, and a completely digested list of grievances, combined, are not enough to adjust a practical reform to its proper work, else Prophets and Apostles and earnest world-menders in general would have been more successful, and left us less to wish and to do.

It is one thing to issue a declaration of rights[2]or a declaration of wrong to the world, but quite another thing wisely and happily to commend the subject to the world's acceptance, and so to secure the desired reformation. Every element of success is, in its own place and degree, equally important; but the very starting point is the adjustment of the reformer to his work, and next after that is the adjustment of his work to those conditions of the times which he seeks to influence.

Those who prefer the end in view to all other things, are not contented with their own zeal and the discharge of their duty to their conscience. They desire the highest good for their follow-beings, and are not satisfied with merely clearing their own skirts; and they esteem martyrdom a failure at least, if not a fault, in the method of their action. It is not the salvation of their own souls they are thinking of, but the salvation of the world; and they will not willingly accept a discharge or a rejection in its stead. It is their business to preach righteousness and rebuke sin, but they have no quarrel with "the world that lieth in wickedness," and their mission is not merely to judge and condemn, but to save alike the oppressor and the oppressed. Right principles and conformable means are the first necessities of a great enterprise, but without right apprehensions and tempers and expedient methods, the most beneficent purposes must utterly fail. Who is sufficient for these things?

Divine Providence has been baffled through all the ages of disorder suffering for want of fitting agents and adapted means. Reformations of religion have proved but little better than the substitution of a new error for an old one, and civil revolutions have resolved themselves into mere civil insurrections, until history has become but a monument of buried hopes.

The European movement of 1848[3] was wanting neither in theory nor example for its safe direction, but it has nevertheless almost fallen into contempt.

We may not, therefore, rely upon a good cause and good intentions alone, without danger of deplorable disappointment.

The reformation which we purpose, in its utmost scope, is radical and universal. It is not the mere perfecting of a progress already in motion, a detail of some established plan, but it is an epochal movement-the emancipation of a class, the redemption of half the world, and a conforming re-organization of all social, political, and industrial interests and institutions. Moreover, it is a movement without example among the enterprises of associated reformations, for it has no purpose of arming the oppressed against the oppressor, or of separating the parties, or of setting up independence, or of severing the relations of either.

Its intended changes are to be wrought in the intimate texture of all societary organizations, without violence, or any form of antagonism. It seeks to replace the worn out with the living and the beautiful, so as to reconstruct without overturning, and to regenerate without destroying; and nothing of the spirit, tone, temper, or method of insurrection is proper or allowable to us and our work.

Human societies have been long working and fighting their way up from what we scornfully call barbarism, into what we boastfully call modern civilization; but, as yet, the advancement has been chiefly in ordering and methodizing the lower instincts of our nature, and organizing society under their impulses. The intellect of the masses has received development, and the gentler affections have been somewhat relieved from the dominion of force; but the institutions among men are not yet modelled after the highest laws of our nature. The masterdom of the strong hand and bold spirit is not yet over, for men have not yet established all those natural claims against each other, which seem to demand physical force and physical courage for their vindication. But the age of war is drawing towards a close, and that of peace (whose methods and end alike are harmony) is dawning, and the uprising of womanhood is its prophecy and foreshadow.

The first principles of human rights have now for a long time been abstractly held and believed, and both in Europe and America whole communities have put them into practical operation in some of their bearings. Equality before the law, and the right of the governed to choose their governors, are established maxims of reformed political science; but in the countries most advanced,[4] these doctrines and their actual benefits are as yet enjoyed exclusively by the sex that in the battle-field and the public forum has wrenched them from the old time tyrannies. They are yet denied to Woman, because she has not yet so asserted or won them for herself; for political justice pivots itself upon the barbarous principle that "Who would be free, themselves must strike the blow." Its furthest progress toward magnanimity is to give arms to helplessness. It has not yet learned to give justice . For this rule of barbarism there is this much justification, that although every human being is naturally entitled to every right of the race, the enjoyment and administration of all rights require such culture and conditions in their subject as usually lead him to claim and struggle for them; and the contented slave is left in slavery, and the ignorant man in darkness, on the inference that he cannot use what he does not desire. This is indeed true of the animal instincts, but it is false of the nobler soul; and men must learn that the higher faculties must be first awakened, and then gratified, before they have done their duty to their race. The ministry of angels to dependent humanity is the method of Divine Providence, and among men the law of heaven is, that the "elder shall serve the younger." But let us not complain that the hardier sex overvalue the force which heretofore has figured most in the world's affairs. "They know not what they do"[5] is the apology that crucified womanhood must concede in justice and pity to the wrong doers. In the order of things, the material world was to be first subdued. For this coarse conflict, the larger bones and stronger sinews of manhood are especially adapted, and it is a law of muscles and of all matter that might shall overcome right. This is the law of the vegetable world, and it is the law of the animal world, as well as the law of the animal instincts and of the physical organization of men; but it is not the law of spirit and affection. They are of such a nature as to charge themselves with the atonement for all evils, and to burden themselves with all the sufferings which they would remove.

This wisdom is pure, and peaceable, and gentle, and full of mercy and of good fruits.

Besides the feebler frame, which under the dynasty of muscles is degraded, there remains, even after justice has got the upper hand of force in the world's judgments, a mysterious and undefined difference of sex that seriously embarrasses the question of equality; or, if that is granted, in terms of equal fitness for avocations and positions which heretofore have been the monopoly of men. Old ideas and habits of mind survive the facts which produced them, as the shadows of night stretch far into the morning, sheltered in nooks and valleys from the rising light; and it is the work of a whole creation-day to separate the light from the darkness.

The rule of difference between the sexes must be founded on the traits which each estimates most highly in the other; and it is not at all wonderful that some of woman's artificial incapacities and slaveries may seem to be necessary to some of her excellencies; just as the chivalry that makes man a butcher of his kind still glares like a glory in the eyes of admiring womanhood, and all the more because it seems so much above and unlike her own powers and achievements. Nature does not teach that men and women are unequal, but only that they are unlike; an unlikeness so naturally related and dependent that their respective differences by their balance establish, instead of destroying, their equality.

Men are not in fact, and to all intents, equal among themselves, but their theoretical equality for all the purposes of justice is more easily seen and allowed than what we are here to claim for women. Higher views, nicer distinctions, and a deeper philosophy are required to see and feel the truths of woman's rights; and besides, the maxims upon which men distribute justice to each other have been battle-cries for ages, while the doctrine of woman's true relations in life is a new science, the revelation of an advanced age, - perhaps, indeed, the very last grand movement of humanity towards its highest destiny, - too new to be yet fully understood, too grand to grow out of the broad and coarse generalities which the infancy and barbarism of society could comprehend.

The rule of force and fraud must be well nigh overturned, and learning and religion and the fine arts must have cultivated mankind into a state of wisdom and justice tempered by the most beneficent affections, before woman can be fully installed in her highest offices. We must be gentle with the ignorance and patient under the injustice which old evils induce. Long suffering is a quality of the highest wisdom, and charity beareth all things for it hopeth all things. It will be seen that I am assuming the point that the redemption of the inferior, if it comes at all, must come from the superior. The elevation of a favored caste can have no other providential purpose than that, when it is elevated near enough to goodness and truth, it shall draw up its dependents with it.

But, however this may be in the affairs of men as they are involved with each other, it is clearly so in the matter of woman's elevation. The tyrant sex, if such we choose to term it, holds such natural and necessary relations to the victims of injustice, that neither rebellion nor revolution, neither defiance nor resistance, nor any mode of assault or defence incident to party antagonism, is either possible, expedient, or proper. Our claim must rest on its justice, and conquer by its power of truth. We take the ground, that whatever has been achieved for the race belongs to it, and must not be usurped by any class or caste. The rights and liberties of one human being cannot be made the property of another, though they were redeemed for him or her by the life of that other; for rights cannot be forfeited by way of salvage, and they are in their nature unpurchasable and inalienable.

We claim for woman a full and generous investiture of all the blessings which the other sex has solely or by her aid achieved for itself. We appeal from men's injustice and selfishness to their principles and affections.

For some centuries now, the best of them have been asserting, with their lives, the liberties and rights of the race; and it is not for the few endowed with the highest intellect, the largest frame, or even the soundest morals, that the claim has been maintained, but broadly and bravely and nobly it has been held that wherever a faculty is given, its highest activities are chartered by the Creator, and that all objects alike - whether they minister to the necessities of our animal life or to the superior powers of the human soul and so are more imperatively needed, because nobler than the bread that perishes in the use - are, of common right, equally open to ALL; and that all artificial restraints, for whatever reason imposed, are alike culpable for their presumption, their folly, and their cruelty.

It is pitiable ignorance and arrogance for either man or woman now to prescribe and limit the sphere of woman. It remains for the greatest women whom appropriate culture, and happiest influences shall yet develop, to declare and to prove what are woman's capacities and relations in the world.

I will not accept the concession of any equality which means identity or resemblance of faculty and function. I do not base her claims upon any such parallelism of constitution or attainment. I ask only freedom for the natural unfolding of her powers, the conditions most favorable for her possibilities of growth, and the full play of all those incentives which have made man her master, and then, with all her natural impulses and the whole heaven of hope to invite, I ask that she shall fill the place that she can attain to, without settling any unmeaning questions of sex and sphere, which people gossip about for want of principles of truth, or the faculty to reason upon them.

But it is not with the topics of our reform and the discussion of these that I am now concerned. It is of its position in the world's opinion, and the causes of this, that I am thinking; and I seek to derive hints and suggestions as to the method and manner of successful advocacy, from the inquiry. Especially am I solicitous that the good cause may suffer no detriment from the theoretical principles its friends may assume, or the spirit with which they shall maintain them. It is fair to presume that such causes as have obscured these questions in the general judgment of the governing sex, must also more or less darken the counsels of those most anxious for truth and right. If our demand were simply for chartered rights, civil and political, such as get acknowledgment in paper constitutions, there would be no ground of doubt. We could plead our common humanity, and claim an equal justice. We might say that the natural right of self-government is so clearly due to every human being alike, that it needs no argument to prove it; and if some or a majority of women would not exercise this right, this is no ground for taking it from those who would. And the right to the control and enjoyment of her own property and partnership in all that she helps her husband to earn and save, needs only to be stated to command instant assent. Her appropriate avocations might not be so easily settled that a programme could be completed on theoretical principles merely; but we need discuss no such difficulties while we ask only for liberty of choice, and opportunities of adaptation; and the question of her education is solved by the simple principle, that whatever she can receive is her absolute due.

Yet all these points being so easily disposed of, so far as they are mere matters of controversy, the advocates of the right need none the less the wisest and kindest consideration for all the resistance we must encounter, and the most forbearing patience under the injustice and insolence to which we must expose ourselves. And we can help ourselves to much of the prudence and some of the knowledge we shall need, by treating the prejudices of the public as considerately as if they were principles, and the customs of society as if they once had some temporary necessity, and so meet them with the greater force for the claim to respect which we concede to them. For a prejudice is just like any other error of judgment, and a custom has sometimes had some fitness to things more or less necessary, and is not an utter absurdity, even though the reason on which it was based is lost or removed. Who shall say that there is nothing serious, or respectable, or just, in the repugnance with which our propositions are received? The politician who knows his own corruption may be excused for an earnest wish to save his wife and daughter from the taint, and he must be excused, too, for not knowing that the corruption would be cured by the saving virtue which he dreads to expose to risk.

There may be real though very foolish tenderness in the motive which refuses to open to woman the trades and professions that she could cultivate and practice with equal profit and credit to herself. The chivalry that worships womanhood is not mean, though it at the same time enslaves the objects of its overfond care.

And it is even possible that men may deprive women of their property and liberties, personal and political, with the kindly purpose of accommodating their supposed incapacities for the offices and duties of human life. Harsh judgments and harsh words will neither weaken the opposition, nor strengthen our hands. Our address is to the highest sentiment of the times; and the tone and spirit due to it and becoming in ourselves, are courtesy and respectfulness. Strength and truth of complaint, and eloquence of denunciation, are easy of attainment; but the wisdom of affirmative principles and positive science, and the adjustment of reformatory measures to the exigencies of the times and circumstances, are so much the more useful as they are difficult of attainment. A profound expediency, as true to principle as it is careful of success, is, above all things, rare and necessary. We have to claim liberty without its usually associated independence. We must insist on separate property where the interests are identical, and a division of profits where the very being of the partners is blended. We must demand provisions for differences of policy, where there should be no shadow of controversy; and the free choice of industrial avocations and general education, without respect to the distinctions of sex and natural differences of faculty.

In principle these truths are not doubtful, and it is therefore not impossible to put them in practice, but they need great clearness in system and steadiness of direction to get them allowance and adoption in the actual life of the world. The opposition should be consulted where it can be done without injurious consequences. Truth must not be suppressed, nor principles crippled, yet strong meat should not be given to babes. Nor should the strong use their liberties so as to become a stumbling block to the weak. Above all things, we owe it to the earnest expectation of the age, that stands trembling in mingled hope and fear of the great experiment, to lay its foundations broadly and securely in philosophic truth, and to form and fashion it in practical righteousness. To accomplish this, we cannot be too careful or too brave, too gentle or too firm; and yet with right dispositions and honest efforts, we cannot fail of doing our share of the great work, and thereby advancing the highest interests of humanity.

.jpg)

,+by+Joseph+Kyle+(1815+-+1863).jpg)