Factory Rules from the Handbook to Lowell, 1848

REGULATIONS TO BE OBSERVED by all persons employed in the factories of the Hamilton Manufacturing Company. The overseers are to be always in their rooms at the starting of the mill, and not absent unnecessarily during working hours. They are to see that all those employed in their rooms, are in their places in due season, and keep a correct account of their time and work. They may grant leave of absence to those employed under them, when they have spare hands to supply their places, and not otherwise, exc ept in cases of absolute necessity.

All persons in the employ of the Hamilton Manufacturing Company, are to observe the regulations of the room where they are employed. They are not to be absent from their work without the consent of the over-seer, except in cases of sickness, and then t hey are to send him word of the cause of their absence. They are to board in one of the houses of the company and give information at the counting room, where they board, when they begin, or, whenever they change their boarding place; and are to observe the regulations of their boarding-house.

Those intending to leave the employment of the company, are to give at least two weeks' notice thereof to their overseer.

All persons entering into the employment of the company, are considered as engaged for twelve months, and those who leave sooner, or do not comply with all these regulations, will not be entitled to a regular discharge.

The company will not employ any one who is habitually absent from public worship on the Sabbath, or known to be guilty of immorality.

A physician will attend once in every month at the counting-room, to vaccinate all who may need it, free of expense.

Any one who shall take from the mills or the yard, any yarn, cloth or other article belonging to the company, will be considered guilty of stealing and be liable to prosecution.

Payment will be made monthly, including board and wages. The accounts will be made up to the last Saturday but one in every month, and paid in the course of the following week.

These regulations are considered part of the contract, with which all persons entering into the employment of the Hamilton Manufacturing Company, engage to comply.

JOHN AVERY, Agent.

Boarding House Rules from the Handbook to Lowell, 1848

REGULATIONS FOR THE BOARDING-HOUSES of the Hamilton Manufacturing Company. The tenants of the boarding-houses are not to board, or permit any part of their houses to be occupied by any person, except those in the employ of the company, without special per mission.

They will be considered answerable for any improper conduct in their houses, and are not to permit their boarders to have company at unseasonable hours.

The doors must be closed at ten o'clock in the evening, and no person admitted after that time, without some reasonable excuse.

The keepers of the boarding-houses must give an account of the number, names and employment of their boarders, when required, and report the names of such as are guilty of any improper conduct, or are not in the as are guilty of any improper conduct, or are not in the regular habit of attending public worship.

The buildings, and yards about them, must be kept clean and in good order; and if they are injured, other-wise than from ordinary use, all necessary repairs will be made, and charged to the occupant.

The sidewalks, also, in front of the houses, must be kept clean, and free from snow, which must be removed from them immediately after it has ceased falling; if neglected, it will be removed by the company at the expense of the tenant.

It is desirable that the families of those who live in the houses, as well as the boarders, who have not had the kine pox, should be vaccinated, which will be done at the expense of the company, for such as wish it.

Some suitable chamber in the house must be reserved, and appropriated for the use of the sick, so that others may not be under the necessity of sleeping in the same room.

JOHN AVERY, Agent

American Textile History Museum

American Textile History Museum

+Woman+with+a+Baby.jpg)

++Shadows.jpg)

+Gathering+Wildflowers.jpg)

+The+Sick+Child+1893.jpg)

+Peeling+Apples.png)

+++The+Cherry+Picker.jpg)

+Spinning+1881+(2).jpg)

+Cabbage+Pickers+1883.jpg)

+Cracking+Nuts+1856.jpg)

+++Home+Comforts.jpg)

+Eel+Spearing+at+Setauket+Fishing+Along+the+Shore+1845.jpg)

++The+Christmas+Day+Turkey+Shoot+(see+Cooper's+Pioneers)+1857.jpg)

+The+Little+Flower+Girl+Gathering+Water+1880.jpg)

+Women+Weaving+Baskets.jpg)

+Tennessee+Woman+1885.jpg)

+An+Important+Letter+1898.jpg)

+Charleston+Vegetable+Woman.jpg)

+Noonday+in+Summer+1852.jpg)

+Kitchen+Interior.jpg)

+A+Serious+Case+1899.jpg)

+Potato+Gatherers+1891.jpg)

+Mother+and+Child.jpg)

+The+Dressmaker+1900.jpg)

+The+Village+Post+Office+1873.jpg)

+One+More+Spoon+1889.jpg)

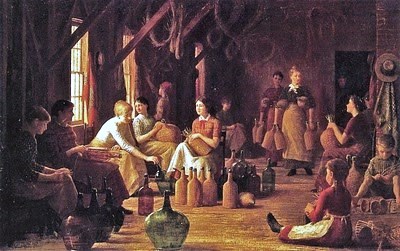

+Flax+Scutching+Bee+1885.jpg)

+Quiet+Time.jpg)

+House+on+the+Hudson+1852.jpg)

+Fortune+Telling+1838.jpg)

+Harvesting+Hops+near+Cooperstown,+New+York.jpg)

+Haying,+1884.jpg)

+Seeking+Advice+(Gathering+Eggs)++1882.jpg)

+Making+Ammunition+1855.jpg)

+Offering+Baby+a+Rose.jpg)

+Hop+Picking+1862.jpg)

+The+Writer.jpg)

+Teaching+a+Child+to+Descend+the+Stairs+1870.jpg)

+Capital+and+Labor.jpg)

+Taken+Captive+By+the+Indians+1849.jpg)

+Coming+to+New+York+for+a+New+Life.jpg)

+Preparing+to+Venture+Out+-+Can+They+Go+Too+1877.jpg)

+Working+in+the+Sitting+Room+1883.jpg)

+Rice+to+Liberty+for+Fugitive+Slaves.jpg)

+Mother+and+Child+1899+(2).jpg)

+Old+Memories.jpg)

+Mrs+Lydig+and+her+Daughter+Greeting+Guests+1891.jpg)

+Catharine+Wheeler+Hardy+and+Her+Daughter+c+1845.jpg)

+Meeting+a+Crisis+-+A+Moment+of+Peril+1890.jpg)

++Collecting+China.jpg)

+Fleeing+the+Plantation+-+On+To+Liberty.jpg)

+The+New+Bonnet.jpg)

+Reading+a+Good+Book.jpg)

+Arriving+in+the+Land+of+Promise.jpg)

+Totally+Absorbed.jpg)

+Interior+of+Maine+Farmhouse.jpg)

+Chess+Players+1891+(2).jpg)

+A+Visit+from+Grandfather.jpg)

+The+Scissors+Grinder+1870.jpg)

+The+Storyteller.jpg)

++A+Country+School.jpg)

+Children+in+a+Schoolroom.jpg)

the-sewing-school-1.jpg)

+The+Countyr+School.jpg)

+The+Noon+Recess.jpg)

+Country+School.jpg)

+Kept+In.jpg)

++Off+to+School+-+A+Breezy+Morning.jpg)

+School+Time.jpg)

+The+New+Scholar+1845.jpg)

+Board+and+Batten+Northern+South+Carolina+Cabin+1886.jpg)

+Cabin+in+the+South.jpg)

+Cabin+Scene+2.jpg)

+Cabin+Scene+13.jpg)

+Cabin+Scene.jpg)

+Cabin.jpg)

+Log+Cabin+with+Stretched+Hide+on+Wall.jpg)

+Louisiana+Cabin+Scene+with+Stretched+Hide+on+Weatherboard+and+Stock+Chimney+Covered+with+Clay+1878.jpg)

+Negro+Cabin+by+a+Palm+Tree.jpg)

+Cabin+in+the+South.jpg)

+Negro+Cabin+with+Palm+Tree.jpg)

+Negro+Cabiin+with+Two-Pole+Chimney.jpg)

,+vol.+14,+p.+49..jpg)

,+vol.+3,+p.+307.jpg)

,+vol_+14,+p_+438_.jpg)

,+p.232.+(Copy+in+Special+Collections+Department,+University+of+Virginia+Library).jpg)

,+p_68_.jpg)

,+p.+177..jpg)

,+vol.+9,+p.+760.+(Copy+in+Special+Collections+Department,+University+of+Virginia+Library).jpg)

,+p_+8_+2.jpg)

,+vol_+19,+p_+726;.jpg)

,+vol.+19,+p.+726;+wiyh+article+by+T.+Addison+Richards,+The+Rice+Lands+of+the+South+(pp.+721-38)..jpg)

,+vol.+19,+p.+729;+with+article+by+T.+Addison+Richards,+The+Rice+Lands+of+the+South+(pp.+721-38)..jpg)

+Scene+in+a+Bar+Room+1845+(2).jpg)

+The+Card+Players.jpg)

+News+About+the+War+in+Mexico+1848.jpg)

+Waiting+for+the+Stage.jpg)

+The+Sailor%27s+Wedding+1852.jpg)

++Self+Portrait+1853.jpg)

+Ann+Old+Coleman+(Mrs.+Robert+Coleman),+c.+1820.jpg)

+Anna+Maria+Eichholtz+1838.jpg)

+Catharine+Hatz+Eichholtz+1833.jpg)

+Clockmaker's+Wife+and+Daughter.jpg)

+Eliza+Jacob.jpg)

+Eliza+Schaum+(later+Mrs.+Frederick+Augustus+Hall+Muhlenberg;+1798-1826)+1816.jpg)

+Eliza+Teackle+Montgomery+1822.jpg)

+Elizabeth+Mrs+Frederick+Augustus+Hall+Muhlenberg.jpg)

+Elizbeth+Hoofnagle+Markley+born+1794.jpg)

+Jane+Buchanan+Lane.jpg)

+Julianna+Hazlehurst,+c.+1820.jpg)

+Mehitabel+Cox+Markoe,+ca.+1815..jpg)

+Miss+Julia+Nicklin+1823+(2).jpg)

+Mrs+Lawrence+Lewis.jpg)

+Mrs.+Elizabeth+Wurtz+Elder+and+Her+Three+Children+1825.jpg)

+Mrs.+George+Musser,.jpg)

+Mrs.+Jacob+Eichholtz+1818.jpg)

+Mrs.+John+Frederick+Lewis+1827.jpg)

+Mrs.+Pierre+Louis+Laguerenne+by+Jacob+Eichholtz.jpg)

+Mrs.+Robert+Jenkins+(Catharine+Carmichael)+1836+(2).jpg)

+Mrs.+Victor+Ren%C3%A9+Value;+Her+Daughter+Victoria+Matilda;+and+Her+Stepson+Jesse+Ren%C3%A9+1826.jpg)

+Mrs.+Walter+Franklin+1814.jpg)

+Phoebe+Cassidy+Freeman+(Mrs.+Clarkson+Freeman),+c.+1830.jpg)

+Portrait+of+a+Woman.jpg)

+Serena+Mayer+Franklin+1838.jpg)

+The+Ragan+Sisters,+1818.jpg)

+Unknown+Sitter+1815.jpg)

Jane+Evans+Tevis.jpg)

Margaret+Hager+Hoff.jpg)

Maria+Schaum,+circa+1810.jpg)

Mrs+John+Gibson.jpg)

Mrs.+Belle+Cohen.jpg)

+Miss-Thomson.jpg)

+Mrs+Longnecker.jpg)

+Rebecca+Trissler+Eichholtz.jpg)

+Self-Portrait+1810.jpg)

+Young+Lady+in+a+Gold+Colored+gown,+her+hair+dressed+with+flowers+and+pearls+c+1820.jpg)

+Girl+in+Blue+Dress.jpg)

.jpg)

+Porcupina+Van+Allen.jpg)

++Lady+in+a+Straw+Hat+1824-1825.jpg)

.jpg)

+conestoga-creek-and-lancaster.jpg)

++The+Trout+Brook+1891.jpg)

+Spring+Blossoms,+Montclair,+New+Jersey.jpg)

+The+Lone+Farm,+Nantucket+1892.jpg)

+Niagara.jpg)

+Early+Autumn,+Montclair+1891.jpg)

Morning,+Catskill+Valley+(The+Red+Oaks)+1894.jpg)

+Near+the+Village,+October+1894.jpg)

+Spirit+of+Autumn+1891.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)